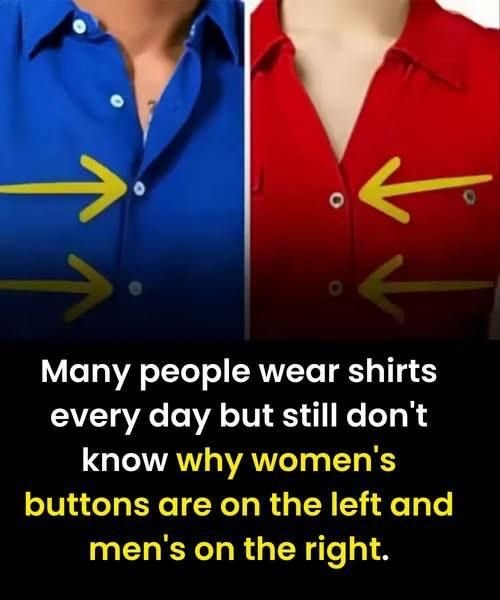

Why do men’s and women’s shirts button on opposite sides? The answer lies not in contemporary fashion but in the dusty corners of social and military history. This seemingly minor design choice is a direct descendant of two very different past realities: one of servitude and status, and the other of weaponry and warfare. This enduring feature demonstrates how clothing is rarely just about covering the body; it is also a record of how people lived, worked, and moved through their world.

For women, the custom of left-side buttons is a legacy of a time when high fashion meant high maintenance. During the height of elaborate dress, a well-to-do woman’s wardrobe was a complex affair. Garments like corsets, gowns, and blouses were engineered with fastenings that were difficult, if not impossible, to manage alone. A lady’s maid was essential. Tailors, considering the dresser’s ease, placed the buttons on the garment’s left side. This allowed a right-handed maid, facing her mistress, to button them quickly and efficiently. This practical accommodation for the helper slowly solidified into a standard symbolizing luxury and a life of leisure, where one was dressed rather than dressing oneself.

For men, the opposite standard emerged from a need for immediate action. The right-over-left closure has its roots in the battlefield and the dueling ground. A right-handed man wearing a sword or dagger on his left hip needed to clear his clothing to draw his weapon without hesitation. A coat or shirt that opened with the right panel overlapping the left enabled him to thrust his right hand across his body and sweep the garment open in one motion, providing unobstructed access. This design, born from martial necessity, was adopted by civilian tailors and became a hallmark of classic menswear, echoing values of functionality and readiness long after the sword was retired.

Today, these historical imperatives have vanished, but the design conventions they spawned remain stubbornly intact. We live in a world of self-service and firearm regulations, yet the gendered button rule persists. It is upheld by tradition, manufacturing habit, and consumer expectation. To deviate from it would feel unfamiliar, even disorienting. This shows the powerful inertia of cultural norms, especially in something as personal and habitual as getting dressed. The original “why” has been forgotten, but the “how” continues uninterrupted.

So, this tiny detail in our daily routine is a silent historian. It tells a story of class division and personal service on one side, and of combat readiness and physical utility on the other. The next time you button a shirt for yourself or a child, you’re not just getting dressed. You’re engaging with a centuries-old narrative, a small but persistent thread connecting the practicalities of the past to the familiar rituals of the present.